Wrestling with Joni Mitchell’s “River.”

Chelsea Biondolillo

*

“Out of sheer rage I’ve begun my book on Thomas Hardy. It will be about anything but Thomas Hardy I am afraid.” D.H. Lawrence

You should begin by thinking, for days, about the sad music you like, and why. Think, specifically, about sad Christmas songs. “River” wasn’t a Christmas song exactly, when written, but it has been drafted into the role by holiday DJs. It’s a natural, after all.

And singing songs of joy and peace

One study posits that people prone to depression tend to think sad music makes them happier, even though it often leads to unhealthy thought processes, chiefly rumination. Ruminate on that for a few days, until the idea of research about sad songs loses its shine. Luckily, a music theory study suggests ways to map emotions in music compositions. Look up what makes sad music sound sad.

I wish I had a river I could skate away on

But first, get hung up on that dangling preposition, on, and how it seems like it shouldn’t work. It just bobs on the end of every verse, and even in the middle of the chorus, where it leads into the line “I made my baby cry” and an odd snatch of melody. Suspect that this line is the real heart of the song—even though it only occurs twice (the second time as “I made my baby say goodbye”) to the seven times “I wish I had a river I could skate away on” occurs. The crying is the thing she can’t stop thinking about.

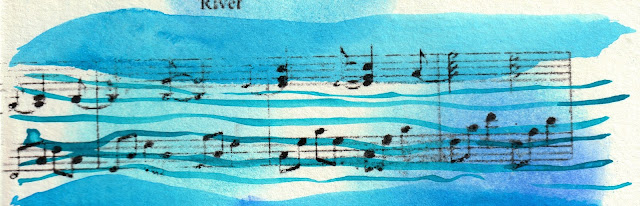

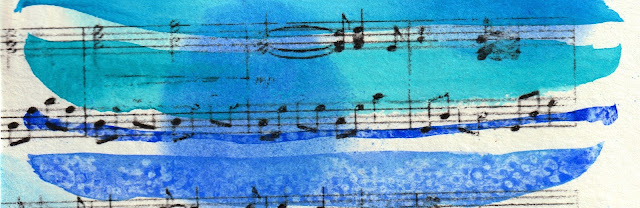

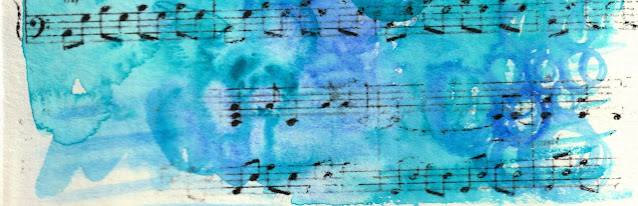

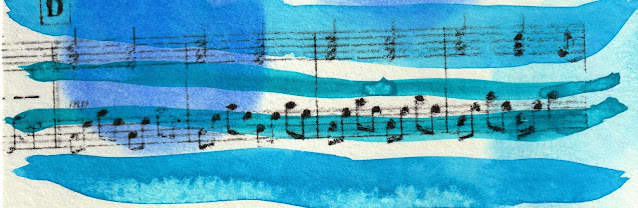

Look up the saddest chord progressions. Look up the song’s sheet music. It’s for piano, which you never learned to play. Decide to look for ukulele tabs so you can learn how to play it. Playing the ukulele is something you have picked up, set down, and picked back up during this longest pandemic season. Think about whether it is the melody or the lyrics that feel the most sad.

Flip the piano sheet music and print it out on your laser printer so you can Xerox transfer it later. Picture something watery. Riverine.

I made my baby say goodbye

Download the Travis version of the song to your phone, because you hate to say it, but you like it (as a sad song) slightly more than Mitchell’s. Count the days you have left to write the essay and at the end of each day, count again. Start a draft about the river you think of as your river, but get self-conscious about opening with any version of “this one time, when I happened to be in New Zealand.” Scrap it.

Isn’t ruminating what essayists do? Wonder aloud whether you have to rethink what you’ve been calling your writing process all this time. Out of sheer melancholy is how you make anything. Out of sheer obsession is how you learn. There is a lot of guilt at the heart of “River” – the urge to run away from the mess you’ve made, rather than face it. Out of sheer remorse.

\When Geoff Dyer couldn’t write his book about DH Lawrence, he wrote Out of Sheer Rage: Wrestling with DH Lawrence, a book about many things besides Lawrence, including about not being able to write. It’s often funny, which helps. It has been suggested to you as a book worth checking out, on more than one occasion, since your inability to write a book on vultures is well documented. Not just vultures, you may feel tempted to scream.

The last time you tried to write honestly about being unable to write, the editor kept sending back the drafts with “needs a more uplifting ending” until you gave up and made up an ending where you could, in fact, write just fine.

Call up one of your best friends, the one who can’t leave the house much lately because of a terrible illness that might be getting worse and that you can’t bear to talk to him too much about, which is selfish, you know. You can’t bear to even imagine a world where he might not be, is why. Instead, play him all the sad chord progressions and ask him to help you figure out whether it’s the chords that make “River” sad.

One site lists the progressions by Roman numerals. Roman numeral one (I) is the root major in a major key, while (i) is the minor root in a minor key, and so on. This site calls vi-IV-I-V the “sensitive female progression.” Get bugged by that. Talk about that music theory class you both took way back in high school, the contents of which he remembers much better than you. That gets you nostalgic (something sad songs do especially well). Think of all the paths you never took. Say something dumb about how now that you are nearly 50, you will probably never move to New York City, and he will counter with how he will never run again, or dance, exactly.

I wish I had a river so long

Spend some time learning two versions on the ukulele, one labeled Joni’s version and one, Travis’. The Travis version is harder to play, but just like the recording, you like it a little better. You always like the harder thing, you will think, involuntarily.

Now you can see it right there on the page, in the Travis version of the song, how the Bm and Dmaj7 chords make the chorus sound a little strange. You note not one, but two suspended 4th chords, each delaying the lyric resolution. That much you remember from music theory.

Spend another week thinking about how your mother will be upset if you write yet another sad essay.

In your notebook write, Can’t this essay be happy? Like Mitchell holding “fly” for nine seconds at 2:20. It sounds like a brief imagining that the narrator, like Icarus in that Jack Gilbert poem, is at the end of a triumph, instead of the beginning of a heartbreak.

Singing the song over and over as you learn to play it will make you think about notable heartbreaks in your life. There’s an unwritten rule that if you need to end a relationship in the second half of the year, you need to do it by Halloween at the latest. Otherwise the pressure of gatherings, feast days, and various and sundry celebrations will keep you lashed together til the end of February. And if you are superstitious about the Ides of March, because of an especially passionate high school English teacher, past even that.

Remember that once, in a December very far from the one presently breathing down your neck, you gave the first real love of your life an ultimatum you knew he wouldn’t accept as a way of breaking up with him. And then in the middle of another December, halfway between then and now, you screamed and shook your fists at a man you’d once said you loved, even though you knew you didn’t. How you wanted him gone—but after New Year’s, you said, because his parents were coming to town and there were so many parties. He was to act decent and not fuck anyone else for just the next two weeks, which it turns out, was too much to ask.

Now I’ve gone and lost the best baby I ever had

Find a podcast all about the song. Hear Joni Mitchell introduce “River” during a live recording, several months before it came out on Blue, an album that NPR has said is “the greatest album of all time made by a woman.” Get bugged by that preposition, too.

“This is a very sad song. Get yourself into a kind of melancholy-before-Christmas spirit, and here we go.” —Joni Mitchell, BBC In Concert, 1970

The podcast features several unrelated people talking about moments in their lives when they connected to “River.” The moments are sad, not unsurprisingly. One man talks about a wild love affair that wrecked him when it ended. He talks about emotional resiliency that comes with age, but uses the term “Thames Barrier” to describe it. You develop a kind of Thames Barrier over time, he says, that keeps your emotions from spiraling out of control. Decide that is maybe something you need. Look up Thames Barrier and watch a few engineering videos about how the barrier works to keep the river open to ships but easily shut off from flooding. That sounds nice, emotionally. Consider, briefly, looking into whether anyone has thought of such a contraption for the Mississippi. But before you can follow that thought, become transfixed by the next video that comes up. It’s on the Falkirk Wheel in central Scotland, which you’ve never heard of. You know about all sorts of insects and animals and rock formations, but much less about great engineering feats.

The Falkirk Wheel looks too fantastic to be real: a spinning boat lift that raises barges and passenger boats nearly 80 feet in the air from one canal to another. You watch its twin arms rotate slowly, as a floating bus of waving tourists bobs slightly in one arm’s gondola. The narrator speeds a fleet of data points by as the wheel spirals up. Only when he gets to the bit about how the two arms of the wheel are always perfectly balanced because they each weigh the same whether there is a boat in them or just water, because of Archimedes’ principle of buoyancy is your attention hooked. A floating object will displace water equal to its weight. You remember learning that a long time ago. Note the metaphor skittering at the water’s edge of your mind.

Allow yourself to get melancholy in that before Christmas spirit, frustrated for the millionth time that you are no closer to a new draft about sad songs, that like the boats riding the Falkirk Wheel, each piece of information entering your brainpan weighs the same amount whether it matters to what you are supposed to be doing or not. Plan to spend some time here, grasping after the heart of the matter and, as if your mind were made of ice, falling through.

*

Chelsea Biondolillo is a collage artist and the author of The Skinned Bird and two prose chapbooks, Ologies and #Lovesong. She is still not the author of a book about vultures and is currently at work not writing a book about reclaiming the house her grandparents built on land in rural Oregon. Her essay “Weeds” won the inaugural Craft Literary Hybrid Writing prize. Currently, she teaches science writing workshops for Creative Nonfiction magazine.

No comments:

Post a Comment