A souvenir postcard, found on the web, says “Don’t think that all the gold/Is treasured in Alaska/For golden corn and Golden Rod/Enrich the state Nebraska.” Goldenrod, named Nebraska’s state flower in 1895, is a drooping profusion of gold that looks an awful lot like a sheaf of wheat. Often mistaken for ragweed, goldenrod is paradoxically the cure for ragweed allergies—a local herbalist taught me how to walk through the prairie in late summer and pick goldenrod at its peak, stuffing the stems into a Mason jar, covering them with Everclear, and letting the medicine cure for six weeks before straining it into bottles and taking a dropperful at a time, as needed. I’ve found the Nebraskan Midwessay to be goldenrod personified: understood only through its oppositional references while its author patiently undoes misconceptions. These essays on the Nebraskan Midwessay may confirm your cliches, but I’d encourage you to look closer: what appears to cause the problem is actually the solution.

Monday, January 31, 2022

The #Midwessay: Lisa R. Roy, Prairie Pioneer

Monday, January 24, 2022

Katherine McCord, An Essay/Review of Sonya Huber's SUPREMELY TINY ACTS

Tiny: I know lipstick is controversial. I wear a kind of mauve pink. You can see me coming. And I don’t care. It’s my armor. I’m on the side of controversy. The other side is harm. I get comments on it. When my color was discontinued, I bought ten tubes on eBay. I don’t know what I’ll do when I can’t find it. There are streaks of it on my books, my papers, my walls, my steering wheel, sometimes in wrong places on my face because I half look when I’m sliding it on. What a good feeling. It’s armor, remember? My cuirass. As close to covering my heart as I can get it.

Tiny: It has to do with my boots. They aren’t leather but cheap ones from Kohls. They were wide at the top and I wanted them snug around my upper calves, so I sent them off and had them tightened. They are so old I’ve had to glue the heels back on with Super Glue and color them with Sharpies, one pair brown and the other black, where the outside is peeling back. I have to color what’s underneath.

Tiny: A long time ago I was on WIC, and now I’m on unemployment. That’s a story I don’t want to go into now because I’m afraid I’ll embellish I’m so mad. It’s kind of like picking up my drugs at the pharmacy this morning. The techs gave me trouble. One bottle contained anti-anxiety meds that basically keep me floating. $90 dollars please. After insurance. What is insurance anyway? Does it really assure you? I don’t understand. I think without insurance the total bottle of pills is $4,000. A friend just lies in bed all the time her hand trailing the floor like it’s a raft going nowhere. Steady, she tells herself trying to sort out her life without the drugs she needs because she can’t afford them. She’s waiting to be cured. Like if the raft sinks and she has to tread water. I think that’s why people steal it. That or just keeping themselves from drowning. She tries healing herself in absolutely every way possible. She scans websites for home remedies. She has a HappyLight that is as strong as they’ll go. She rolls off the raft and swims to the refrigerator and back.

Tiny: This is an essay/book review about Sonya Huber’s latest book, Supremely Tiny Acts (2021). So far, we’ve followed her go over her past showing the “tiny” pieces of her life in profound and almost loving frustration. She gets arrested for demonstrating. Despite it being somewhat minor, the ordeal lasts two days. She sits in cells for long times, she rides in a paddy wagon, some of her fellows have glued their hands to a boat. There are more ordeals and many flags and signs, in that they are impossible for each person to hold in their number of placards. But she does it. It is extremely painful for her being cuffed by a zip tie behind her back. When she arrives, for an unorganized court, after many hours, there is no pronouncement that she and her comrades are free, but they are. She takes the long ride home, entailing trains and busses and her car, to pick up her son, just in time for his driver’s license test.

Sonja weaves in heartfelt and seeming-to-be secrets, in that they are intimate, among the happenings of the two days: “[W]orst case” scenario is that “people won’t approve of me” she says. For her actions, for her teaching, for her mothering, for her being a partner. But because of the intimacy she offers us, she shows us she is: She tells her partner, who already knows, “this was going to be a tiny opportunity for disaster,” for what she is about to undertake. But also, even much, much tinier, the littlest things: Google calendar. She can’t handle it. Dates get transposed and the debacle goes on. There are those words again, “tiny” and “acts,” that make up a life of being very conscious, very concerned with following the rules of two days, everything, and “wanting to break them at the same time.”

Tiny: Once I attended a workshop for graduate school the fees for which we are still trying to pay off. I sat unknowingly next to a faculty member, he had placed his notes on the round table. I didn’t know they were his or that it was his smooth white chair next to mine. I didn’t see anything but that he had written, “POWERFUL,” and circled it in several deep rings next to my poem. He was still in the hall talking away to one of his rock stars. Later my poem would be sucked up by or fall into a black hole, perhaps by choice. The workshop begins. My poem wasn’t worth anyone’s time it was so bad, they said. He never spoke a word during the whole time but slid his notes away because he was afraid I could see, as if he was ashamed. Workshop over, I stumbled out as if I was tumbling over a rocky terrain, found a gray empty bathroom, my ship, then an ejection stall, my booth within, and wept as softly as I could, then drew a blade up my cold arm just underneath my coat I always wore because I was perpetually cold. It helped me just enough to release and spin.

Tiny: I cut back the stems on some flowers my mother-in-law sent for Thanksgiving. They were beautiful and the colors of fall. I’m trying to keep them going as long as I can. My mother told me you can by snipping their stems back under running water once they start to turn. Sonja Huber’s book, Supremely Tiny Acts, won’t “turn.” The acts written with strength and clarity will make you want to live within.

*

Katherine McCord is the author of two books of poetry (Island and Living Room), a lyric essay memoir, (My CIA), a poetry chapbook (Muse Annie), and a literary memoir, Run Scream Unbury Save. My CIA was named a top ten book of 2012 by Review of Art, Literature, Philosophy and Humanities and added to their ongoing list of Great Nonfiction. She teaches Creative Writing, both online and in the traditional classroom, for credit at universities and noncredit for various worthy online venues, to all kinds of student populations.

Monday, January 17, 2022

Cheryl Graham, I ♥ the 80s

We had so many great cover essays for this year's Advent Calendar that we decided to make it a regular (if occasional) feature. So expect more cover essays in 2022 and beyond. And if you've got a cover essay or an idea for a cover essay, pitch us (email Will or Ander, or ping us on twitter). —Editors

⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯

In the eighties I played in a band. I was the only girl. I was frequently troubled by the Reagan presidency, the looming threat of nuclear annihilation and, as Prince put it, “a big disease with a little name.”

When Reagan denounced Russia on a hot mic and said “we begin bombing in five minutes,” I became afraid to sleep alone.

I attended gigs by local bands, out-of-town bands, and national touring bands. I sometimes camped out to buy tickets. Staying up all night was not a problem for me.

I wrote bad songs.

I went to school—The University of Arizona—much of the time.

I read music magazines the way people suck candy.

Personal relationships were more important to me than anything else.

I was enthralled by an older woman. She was 21 and married to an even older man. We drank vodka and lay on the floor of her living room in the dark and listened to David Bowie sing “Cat People.” Instead of putting out fire with gasoline, we sang Vaseline, and rolled over laughing. I don’t remember the first time we kissed, I only remember the feeling of wanting to.

I had personal relationships with sorority girls, photographers, high school kids, alcoholics, non-specialized acid casualties, and numerous poets.

With three other students I lived in a rented bungalow south of campus. One roommate kept a St. Bernard and sold drugs. The St. Bernard bit me in the back, and its owner said he would euthanize it. He moved out so I never knew if he really did.

I knew a professor of Art History who created erotic performance art in which she read feminist theory in various states of undress.

In the eighties there were always parties. Before we went to the parties, we’d stop by my friend Lisa’s ex-boyfriend’s house for Quaaludes. The pills were still legal and Rick James referenced them in “Super Freak.” After I started sleeping with Lisa, the ex-boyfriend would call me on the phone and talk for a long time. After she broke up with me, I’d call him on the phone and talk for a long time.

I took classes in drawing and English. I took classes in linguistics, women’s studies, and modern art. I studied painting and French and wrote songs about French paintings.

Inside the Controversy album was a poster of Prince standing in the shower wearing only a g-string and a gold chain around his hips. I hung the poster in my bathroom. When he played in Phoenix, I rode to the concert with a friend in the back seat of another friend's car, mixing gin and tonics. The friend drove eighty-five miles an hour and drafted behind a semi so closely the trucker couldn’t see our car. We had a little cutting board in back for the limes.

My band practiced in a dusty garage and listened to Joy Division, the Gun Club, and the Fall. We wore secondhand paisley shirts and penny loafers with no socks. I took Black Beauties every day for a week, then slept for two days after that.

I had asymmetrical hair.

I walked into a pink stucco house one afternoon and met a woman named Liz. She had just come back from Europe, and for that reason would only drink Heineken. We hiked up Sabino Canyon and cooled the beer cans in the creek. When we moved in together, I hung the Prince poster in the bathroom.

Eventually I got in a different band with different boys and took a semester off to go on tour. I didn’t withdraw from classes, I just stopped going to them. I got F’s in everything except Painting. On the road we listened to the Human Hands, Zoviet France and The Violent Femmes. We slept on the wooden floor of a loft in San Francisco that had been occupied by a man who hanged himself.

Ian Curtis had also hanged himself and I thought, somehow, the two suicides were connected.

I protested the escalation of the Cold War. I marched to Take Back the Night. I thought Mondale could win.

I heard the Smiths for the first time in a dorm room at UC San Diego, where my band played to ten people at the Ché Café. When I came home from touring, Liz told me she hadn’t slept with our mutual friend yet, but she wanted to. I moved out one afternoon while she was at work.

I got a job at the daily newspaper and was fired two weeks later for being “too artistic.”

I went to work in a coffeehouse. At night we listened to Gene Loves Jezebel and flirted with all the people coming in after the bars had closed. I worked with a boy from Arkansas named Jeffrey who wore those deep V-neck sweaters from the Gap with no shirt underneath. He shaved his chest and dyed his hair red. He moved to San Francisco and not too long after that, somebody saw him in a porn magazine.

I used to think that someday I would write a film version of my stupid life in the eighties.

I dropped LSD for the first time with a customer from the coffeehouse. Somebody said the guy had so many library fines that the University wouldn’t grant him his diploma. So he just bought one cup of coffee and sat in the corner all day and tried to make friends with the lesbians.

On the day we took acid, we rode the elevator to the top of the Science building and found an open door to the roof. There was a monsoon sky and I saw God in the clouds. God was Aretha Franklin and she had two backup singers. Somewhere I read that when they made the video for “Sisters Are Doin’ It for Themselves,” Aretha wouldn’t talk to Annie Lennox because she thought she was gay.

I hated that song.

Eventually I had friends in New York, Cambridge, Seattle, Portland, & Los Angeles.

I had a coworker, Patrick, who was an astonishingly attractive man from New England. He had slate blue eyes and a patrician jawline, and the cultivated stubble of a Ralph Lauren ad. If he told you to go fuck yourself, you’d think he paid you a compliment. When I had to open the shop in the mornings, he’d get there early and do all the work and meet me at the door with a cup of tea. We’d listen to Kate Bush in the calm early light and wait for the morning rush. When Kate sang “Wuthering Heights,” a customer would invariably come to the counter to inform us the record was on the wrong speed. I loved watching Patrick tell them it was supposed to sound like that, then roll his eyes at me as the philistine walked away.

After he got sick, Patrick moved back to Boston and wrote me type-written postcards. When I got the news he had died, I was lying in bed waiting for a pizza delivery. The eighties ended that night.

*

Cheryl Graham lives in Iowa City. She writes about music for PopMatters, and has been published in the New York Times, Sierra Magazine, Pigeon Pages, and the March Xness series.

Thursday, January 13, 2022

Sean Lovelace's Classic Essay, "Total T-Rex"

We had so many great cover essays for this year's Advent Calendar that we decided to make it a regular (if occasional) feature. So expect more cover essays in 2022 and beyond. And if you've got a cover essay or an idea for a cover essay, pitch us (email Will or Ander, or ping us on twitter). —Editors

⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯

“Seeing a chicken egg bears the same relation to seeing a dinosaur egg as kissing a man does to marrying him.”

A gigantic polypropylene Tyrannosaurus rex in Bowling Green, Kentucky, on March 20, 2015 (Bebe Barefoot / Stringer / Getty)

⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯

2022

⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯

Ever since it was first published in 2019, readers—including this one—have thrilled to “Total T-rex,” Sean Lovelace’s masterpiece of literary nonfiction, which describes his family’s quest to witness a gigantic polypropylene Tyrannosaurus rex in rural Kentucky. It first appeared in Lovelace’s landmark collection, Teaching a Stick to Fart, and was recently republished in The Abundance, a new anthology of his work. The Atlantic is pleased to offer the essay in full, here, until the end of the pandemic. —Ross Andersen

⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯

It had been like dying, that eating in the Bowling Green, Kentucky Pizza Hut. It had been like the death of someone, maybe the cockroaches that littered the floor like cockroaches, maybe the cigarette butts, maybe the tremulous saliva-like sheen of grease on the table my two kids enjoyed as it made for excellent lubrication for the sliding of salt and pepper shakers off onto the cracked tile floor. Someone was whimpering, perhaps the waitress. Her mouth looked like a hole you fall into while sleeping. No, it was my wife. She was looking at her iPhone and whimpering over a video of a bunch of hummingbirds at a birdbath. It was a pretty moving video. After an hour the pizza arrived, cold and simultaneously burnt and then the bill showed up like a whispered curse on a greasy plastic bill-holder tray that someone (or thing) had chewed upon, and I drank 7 diet Cokes (I was trying to stop drinking and the professional golfer, John Daly, has said if you consume diet Cokes all day long you can stop drinking…) and it had been like dying. Dinosaur World we had traveled here to see sat and belched in our minds like a smoldering meteorite crater nine miles away down highway 65.

This article is adapted from Lovelace’s recent book.

I lay in bed. My wife, Gary, was reading an article on her phone beside me. I lay in bed and looked at the painting on the hotel room wall. It was a print of a lifelike and eudemonic painting of a smiling clown’s head, made out of bocce balls and items from a kitchen drawer. I lay in bed and contemplated how I used to be really good at bocce, even playing semi-pro for several years on the Minestrone Circuit out of Northern Boston (bocce is an Italian game). It was a simple honest living. A bocce ball held in hand has a comforting heft. It is like holding a Zippo lighter or a river stone or a mashed bag of cannabis gummies you might have hidden from your family in an internal compartment (you cut with a pocketknife) in your shaving kit next to possibly some Dexedrine—it just feels right. Two years have passed since the gigantic polypropylene Tyrannosaurus rex of which I write. During those years I have forgotten, I assume, a great many things I wanted to remember—but I have not forgotten that clown painting or its lunatic setting in the highway motel or the way crushed and snorted Dexedrine will cake up in your sinuses like desiccated drywall. The clown's head was a bald bocce ball, but I already mentioned that. His hair was bunches of tangled phone chargers. Inset in his white clown makeup, and in his bocce ball skull, were his small and laughing human eyes. The clown’s glance was like the glance of Rembrandt or Hannah Montana: lively, knowing, deep, and loving. His eyebrows were rubber bands. Each of his ears was a miniature stapler. His thin, joyful lips were credit card receipts. The clown print was framed by either cheap aluminum or the abyss.

⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯

“Each of his ears was a miniature stapler.”

⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯

To put ourselves in the path of the gigantic polypropylene Tyrannosaurus rex, that day we had navigated five hours inland from the Muncie, Indiana coast, where we lived. Like Roethke, “I take my driving slow.” When we tried to cross the Lewis and Clark Bridge over the Ohio River, a pedestrian had blocked the pass with his turd brown rusted pickup truck.

Traffic backed up. A skinny man with no shirt and huge ears was trying to duct tape some kind of plastic (garbage or grocery?) bag over his license plate. We waited as cars halted into a jam and idled emphysemic, the whole time the man busily awork on his task. He seemed intense; a man who stalks his calling like a Blue Heron or a Zen monk. Once the man reentered his truck and rattled across and traffic loosened, I understood. The bridge had robotic cameras perched all over its beams like Orwellian crows. This was one of the new toll bridges, with zero human contact, just a bill ($4.22 per axle) arriving in your mail and not even a thanks for passing by. Did I consider the man demented to stop in the middle of a highway, hold up hundreds of cars, and hide his license plate? At first, yes. Later, as I ruminated and my lungs hushed in awe, no. He was a hero. We drove over the Ohio River and descended several feet into central Louisville and its mythical racetrack, Churchill Downs, where I once happily lost $114 and my pants. (I was on a three-day bender during a writing conference). As we shed altitude, the city disappeared; our ears popped; the trees appeared, and I rolled down my window. Above the trees were spirals of birds flying backwards and honking in a strange metallic trilling. Have you ever heard migrating Sandhill Cranes? They sound like Martians and are weird as fuck. I listened to the birds innocently, like a fool, like a raptured diver in the rapture of the deep who plays on the bottom while his air runs out, rapturedly.

⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯

“They sound like Martians and are weird as fuck.”

⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯

The motel lobby was like every motel lobby off a Kentucky highway that has ever existed. The skinny manager had long hair and enormous breasts, just like Clara from the Bolaño short stories. I had an urge to live with her. She said our room didn’t have a TV but there was one in a box—she gestured to an enormous, crumpled cardboard box that said SONY—right over there if we wanted to carry it upstairs ourselves. The box was darkly stained, as if oil had leaked down one side. I have lower back pain and a popcorn knee. At the dim far end of the room, their backs toward us, sat six bald old men in their shirtsleeves, around a loud television showing America’s Got Talent. There was a neatly dressed kid on the screen, either eating or riding (I couldn’t tell which) a bicycle, but somehow suspended in the air above Simon Cowell and the other two judges. One of the judges appeared to be asleep. “Do it again!” cried Simon on television, “Do it again!”

Stranger at unknown motel, unknown location, on July 4 2008 (Julio Jones / Stringer / Getty)

Now the alarm was set for 6. Like Roethke said, “Sleep or roses?” Dinosaur World didn’t open until 10, but Gary would want to do something complicated to her hair, the kids would desire breakfast (I never eat anything but diet Coke and Dexedrine until lunch) and I wanted time to complete the New York Times crossword puzzle and then 50 pushups and flex in the mirror with my shirt off. I lay awake remembering an article I had read on my phone while using the bathroom, in National Geographic. The article was about a South American tribe of cannibals.

⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯

“’Do it again!’”

⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯

The article read in part: “The cannibals dance around the explorers. The cannibals light the fire. The cannibals have their faces painted in three colors. The cannibals prefer the heart and brain, disdaining the tender flesh of the thighs and the leftover intestines. The cannibals consume those parts of the body they believe will instill in them the virtues they admire in their victims. The cannibals partake of their ritual banquet without pleasure or mercy. The cannibals don the explorers’ clothes. The cannibals, once in London, deliver scholarly lectures on cannibals.”

Early the next morning we checked out. We would drive out of town, find Dinosaur World, locate the gigantic polypropylene Tyrannosaurus rex, and then drive back over the river and home to Muncie. How familiar things are here; how adept we are; how sumptuously and professionally we check out! I had forgotten the clown’s smiling head and the motel lobby as if they had never existed. Gary put the car in gear and off we went on another of our many adventures! (Just in the last year, we’d taken the kids to a corn maze in Illinois and later to Corpus Christie, Texas, to lay a rose at the grave of Latin American crossover phenomenon, Selena.)

It was dawn when we found highway 65 and drove into the unfamiliar countryside. By the growing light we could see a band of clouds in the sky. One of the clouds looked like a silver gravy bowl and a beechwood warming stand from the era of Louis XV; the other one looked like Facebook.

* * *

The parking lot was 501 feet long. Stunty arborvitaes lined its border, an evergreen tree very similar to the ones we planted back home to block the persistent western winds. One sultry day last August Gary had mentioned we should cut down two of the arborvitaes for a better view of an old barn in the distance and I replied, “Every one of those trees most likely contains a bird nest in its hidden core. How many nests in this world will we obliterate to see the barns? How many, Gary?” Gary gave me a look she often gives me: quizzical distaste. “I have no idea what you are talking about,” she said and took a long draw on her bottled water. “God save our life!” I spat back. Later that evening I beat her in trivia (I haven’t lost any form of trivia in eighteen years) and then we made awkward love and slept.

East of us rose the gift shop and three ticket kiosks painted a garish blue and yellow. (I found out later these are the state colors of Kentucky.) We tightened our scarves and looked around. Then we paid ($15.75 adults, $12.75 kids) an expansive woman named Debra Leroy to get our tickets. Leroy had a sweater with a purple stegosaurus on it in glitter and crazy pink and gray hair that made me envious and reminded me of an accident I’d witnessed once as a child wherein a hot air balloon snagged on some overhead wires while descending and tumbled into a water treatment facility. Leroy said her people live over in the hollars near Clinton County and her mom was hit by an Amazon delivery truck and her dad had colon problems and her brother joined a cult and her sister just lost her job in the coalmines and all three of her kids were serving in the Coast Guard clear over in Virginia and where did we come from anyway? Indiana! Lord. Leroy said have fun. Leroy said avoid the Porta John by the velociraptors. Leroy said the best spot for shade was under the pregnant triceratops. Some people kiss under its butt! Leroy caught my eye and winked. Leroy said take a picture. I thought, I would like to learn, or remember, how to live.

⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯

“Some people kiss under its butt!”

⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯

Now the sun was up. Tendrils. More people were parking in the lot and clamoring nearby. All of us rugged individualists were wearing khaki cargo shorts and New Balances. It looked as though we had all gathered in a Jurassic world to pray for the planet on its last day. It looked as though we had all crawled out of spaceships and were preparing to assault the gift shop. It looked as though we were about to sacrifice virgins, make rain, eat cake, bang a gong, sauté kale, pound sand, throw dice, swim a length, cut a rug, return the ring. There was no place out of the wind.

My kids did what they always do in a gift shop: ignored the stuffed brontosaurs toys, fossilized shark teeth, fake dirt, Dinosaur World lint removers, etcetera, etcetera, and bought some candy. Gary got a tie-dye (she loves anything tie-dye) DINO WORLD T-shirt. I purchased four 20 oz bottles of diet Coke and slipped two each in the front pockets of my shorts.

I went to the bathroom with my shaving kit I had stuffed into my fanny pack. Then I bought another diet Coke and we stepped out back of the gift shop, onto the picnic grounds, where several fellow explorers milled about smoking cigarettes and eating popsicles in the shape of a Dilophosaurus. Wind. Deep blue body of sky. Clouds. Gossamer. And a hawk screamed overhead, and I flinched and pointed at the ground and shouted, “Weasel! Weasel! Weasel! Weasel! Weasel! Weasel! Weasel! Weasel! Weasel! Weasel! Weasel! Weasel! Weasel! Weasel!” People froze. People stared. It was not a weasel; it was a brown Miller Lite beer bottle at the base of a garbage can. “Sorry,” I mumbled. And then, behind a small security roping, I saw the egg. The egg. So.

⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯

“So.”

⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯

I had seen a chicken egg in 1984. A chicken egg is very interesting. It bears almost no relation to a dinosaur egg. Seeing a chicken egg bears the same relation to seeing a dinosaur egg as kissing a man does to marrying him, or as flying in an airplane does to falling out of an airplane. Although the one experience precedes the other, it in no way prepares you for it. A sign read OVIRAPTORID EGGS DO NOT TOUCH. My kids immediately climbed over the roping and vandalized the eggs. Holy shit!

“Get them! Gary!!!!!!!!!”

Photo credit, Gary

From all the picnic grounds came screams. A piece of blue beside the Dippin’ Dots was detaching. Security guard!? My heart kicked up like two artic terns tumbling in a mating ritual. Tremors. My mouth went Moroccan sand. My brain a loosened circle of evening sky, suddenly lighted from the back. A body rushed! It was an abrupt blue body out of nowhere; it was a barreling SWAT team; it was a squad of fallen angels! It was lava dragons! It was almost over my children, the eggs! That is why there were screams. No. I smelled charred meat on the wind. Primeval fire. At once this smoke of acidic (dill?) relish slid over the air like a lid. The hatch in the brain slammed. Abruptly it was now the scent of bread, not relish, on the air and on the land and in the sky. A tiny ring of laughter. Parenting is hard. The holding of my hands where my children belonged. There was no sound. The eyes watered, the arteries drained, the lungs galloped. There was no world but cave. My hands were clay. My mind was going out; my eyes were receding the way manatees recede to the rim of seas. We were the world’s bad parents rotating and orbiting around and around, embedded in the prehistoric crust, while the Earth rolled down. Thoughts were light-years distant, forgetful of almost everything. We had, it seems, loved our children and loved our lives, but could no longer remember the way of them. We got the generations wrong. I missed my own century. I missed nachos and electricity and Netflix and driving the kids to school. In the back of my head was a Frisbee of light. It was a thin ring, an old, thin silver wedding band, or maybe a pacifier or a vape pen. I smelled mustard. There were stars. It was all over.

______________

“I missed nachos…”

______________

“Are you okay?” a voice said. I was on my back, with Debra Leroy standing over me, blocking the sun like an archipelago. Her perfume smelled of rotting fruit.

“Um, yeh,” I said, rising up to my elbows. Spin, spin slowing. My mouth felt like an athletic sock. “I’m fine.” I stood up and brushed myself off and grinned stupidly.

“Alrighty then,” Leroy said, and handed me a hot dog. “This one is on the house. People always forget to eat before they come out here, excited and all. You’re not the first I seen faint right out.”

“Thanks,” I mumbled. Leroy just shrugged and waddled off to the gift shop. The hotdog was moist and toasty.

Gary walked up and said, “Well, they pulled the T-rex. Guy over there told me kids and drunk tourists kept climbing it and falling off. Some kid broke his back. He said they had a big crane in here and yanked it out two years ago. Also said I had a nice ass.”

“Pulled it?” I said through a mouthful. It was a very good hotdog.

Gary said, “The lawyers. They pulled it. Fucking lawyers…” She shook her head. ‘This is why we can’t have nice things.”

* * *

It is now that the temptation is strongest to flee these regions. We have seen enough; let’s go. Why stain our hands with condiments any more than we have to? But two years have passed; the price of gas and toilet paper and diet Coke has risen. Seeing my own blood swallowed by that dinosaur egg was like seeing a mushroom cloud. The heart sneezed. The individual heart is as small as one goose in a flock of migrating geese—if you happen to notice a flock of migrating geese. The event obliterated itself. Yet I return to the same picnic tables and pick through the smeared ketchup again.

We teach our children one thing only, as we were taught: to eat. I do not know how we returned to the Pizza Hut. Like Roethke, “I fog the spatula.” Gradually I seemed more or less alive, and already forgetful. It was the day of a dinosaur egg in central Kentucky, and an educational adventure for everyone. It was now almost evening. The sky was dusky; there was an odor of breadsticks out of the north. We ate our fill and then more than our fill, as is our way. I was on my third slice of deep dish and eleventh diet Coke. The kids chewed on candy. Gary had spaghetti. We paid. Oh, we paid. We found our car; we paused to watch a kid repeatedly slamming a shopping cart into the brick wall of Pizza Hut, bam, bam, bam; the kid was giggling and was either very dumb or a contented genius. We pulled away, joined the highway traffic, and drove for home.

______________

This post is excerpted from Lovelace’s book The Abundance: Narrative Essays Old and New. Copyright © 2021 by Sean Lovelace. Published by arrangement with Echo, an imprint of HappyGilmore Publishers.

*

Sean Lovelace lives in Indiana, where he chairs the English Department at Ball State University but is best known for his pioneering work on the theoretical intersections of the natural world and nachos.

Saturday, January 1, 2022

The 2021 Christmas Octave: MARTHA STRAWBRIDGE, An Incompleteness Theorem

- If I find my way to the end of this proof, then I will have proven a theorem, even if I don’t know how to name it.

- If I prove this theorem, if I prove all my theorems, then I might, like Pitkin, be able to string my results across an essay.

- Then the proofs themselves will become the story I tell myself.

- If I am able to write this story, then I too, might be able to write you are alive, and then, you will come home whole.

- And if you will come home whole, then you will come home sober, finally.

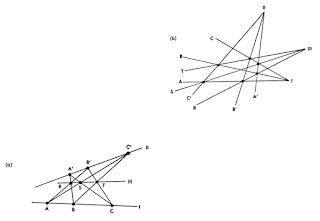

- If I approach the parallels in this proof, then I will learn it is impossible to prove that parallel lines are everywhere equidistant.

- If I accept this impossibility, then I will have reached the limits of my logic, where I must choose between contradicting myself or accepting a new axiom.

- If I am forced to choose between inconsistency and incompleteness, I will have to accept the latter; that is, I will have to accept that I can’t know everything.

- If I accept that I can’t know everything, I will have to operate on a degree of faith.

- If I am enamored by the tools of mathematical proof, then I am beholden to the extremes of logical quantifiers.

- If I am bound to these quantifiers, then I am inescapably aware of each “for every” and “there exists” statement that could undo the foundations of our mutual trust.

- (As in, for every year that we remain together after this summer, there exist 356 days on which you might relapse, on which I’ll stop trusting you, on which you’ll stop trusting me to trust you.)

- And if I am aware that our foundations are in a perpetual state of potentially going to ruins, then I could imagine myself refusing to build any lasting theorems upon them.

- If there are no more theorems, then there are no more proofs, and no prayers.

- If I am enamored by the tools of mathematical proof, then I am enamored enough to believe that these tools are capable of withstanding my bastardization of them.

- If I can trust myself to bastardize the proof, then I am willing to trust my bastardization of the axiom, too.

- (As in, I can call the symbols meaningless and the truth will persist, I can destroy the image but not the object, I can distrust the blueprint but the foundation will remain intact.)

- And if I can accept my incomplete trust in the axioms, then I can accept that each proof is proof as prayer.