*

Amy Wright is curious.

She wants to know everything about those who surround and inspire her, even an ambitious spider that, in a feat of engineering, spins a fifteen-foot web from a backyard tree branch to the eave of the roof above the window by her writing desk. What sets Wright apart is that she doesn’t just marvel about the spider’s accomplishment to herself for a moment; she stops what she’s doing, she goes outside, she investigates, she records, she remembers. And then she integrates what she learns into her identity.

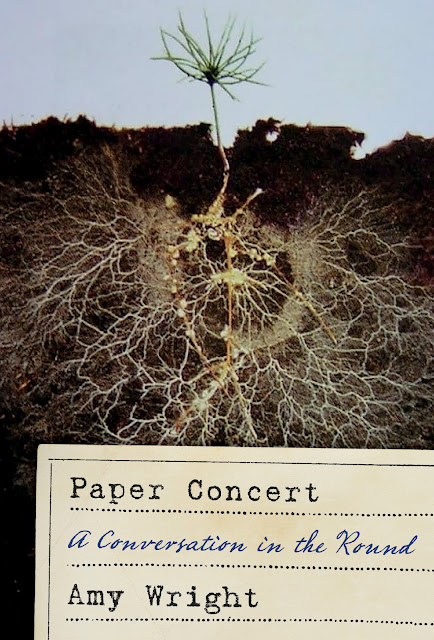

In her most recent book, Paper Concert: A Conversation in the Round, published by Sarabande Books, readers get a front-row seat to Wright’s curiosity in action as she shares portions of over fifty conversations with artists, activists, scientists, philosophers, physicians, priests, and musicians. About the people she interviews, she says “Some are famous, some will be, some should be—but all of them refract the light of the unknowable mystery of the self.” Gathered over eleven years, these conversations stem from a question she has asked herself since childhood: What am I?

As the conductor of this Paper Concert, she showcases the gifts and insights of others, including writers Dorothy Allison, Dinty W. Moore, Sejal Shah, and Ira Sukrungruang; artists Marc Gaba and Raven Jackson, scientists David Haskell and Tim Flannery, and many more.

What underlies their insights is Wright’s desire to know and understand the world around her and, of course, herself. Along the journey, the reader receives an unexpected bonus.

Wright flips the script on the traditional Q-and-A interview format. In Paper Concert, the reader doesn’t immediately know who is being asked what.

White space—like a curtain opening and closing—separates the questions from the names of the interviewee and their answers. The unpredictable pattern of interviewees gives the reader an opportunity to pause and consider the questions first for themselves.

What’s your favorite joke? How do metaphors contribute to your mode of thinking? How do you feel about ketchup? How does time enter art? What was your first job? Have you ever seen a ghost? Do you collect anything? Why were you attracted to your first boyfriend? How does a robot become more human than humans? What justifies your optimism? If you had to set fire to something, what would you burn?

The effect is that the reader becomes part of the concerto, adding their voice to the chorus.

Within this composition, solos rise and call attention to particular interviewees via questions about their specific work: It is not a given, you write, “that the heart is lonely and so must live forever.” What is a given?; How did your identity as a Native person shape your sense of self?; You lived in a papermaking village in Japan in the late seventies. How did living there shape your aesthetic?

Questions like these encourage the reader to pause and reflect while simultaneously boosting curiosity about the response from the yet-to-be-revealed interviewee. We’re invited to take time to slowly unwrap each gift, savoring the moment of expectation.

As what happens in conversations, not all questions appear as questions. Some take the form of statements that spark deep responses: You demonstrate the complexities of class anger through your characters and Your first writing teacher, Bertha Harris, told you, “Literature is not made by good girls.”

As readers gain insight from others about topics such as poverty, dance, queerness, neighborliness, cancer, and racism, they also learn about themselves—a gift Wright bestows on us.

Here’s the question she asks most often: When have you felt the freest?

Wright herself answers this question through her exquisite interludes between question-and-response sections. Many of them depict scenes from her childhood and young adulthood that showcase moments of both fear and freedom—fear stemming from uncertainty (of the dairy cows who watched her, of the Jackson boys who teased her, of her college roommate Manda who broke rules Wright had been taught) and freedom often grounded in nature through scenes of her younger self on her family’s farm in the Blue Ridge Mountains.

Her curiosity about others boosts our curiosity about her, and I’m grateful for the opportunity to ask her a few questions.

Jenny Patton: According to writer Joseph Heller, “There was no telling what people might find out once they felt free to ask whatever questions they wanted to.” Do you feel a sense of freedom when interviewing others? What response in the book most surprised you?

Amy Wright: I love this question, thank you! It is indeed freeing—and a great privilege—to wonder. But we might also think of marvel as an obligation toward the communities we want to participate in and create, given that Toni Morrison said, “The function of freedom is to free someone else.” Our questions grow broader, more generous, and freer, when asked with that goal in mind.

Surprise was one of the rewards in every conversation that became this book. Everyone I spoke with, at some point, shifted my expectations. My favorite moments came when they surprised me with a story—as when Dinty W. Moore described being a zookeeper to a female gorilla who developed a crush on him. I also loved those happy chances when stories opened windows into someone’s life, as when Ander Monson describes receiving a mysterious cassette that illustrates his friendship with Michael Martone. Since Martone is another of the book’s contributors that surprise felt like kismet.

You describe your younger self as a “reticent farm girl” and share that part of your desire to learn all you could derived from fear. Now that you’ve completed this “survivor manual,” what’s your relationship with fear? What else do you still want to learn?

Finding great answers emboldened me to keep asking hard questions. I have also grown unexpectedly fearless when others ask questions of me now, since I have a storehouse of responses at the ready. But the key insight of this book is how much more important than any manual or guide is an active witness to evolve our questions using the raw material of previous answers given across time.

I’m curious now how different questions—and new literary forms—can change the nature of our conversations, expand access, invite new voices, and deepen intimacies over the networks that technology has created globally.

You asked Lia Purpura if she follows any advice columnists. In some ways, Paper Concert itself serves as an advice column—not only for artists but for us as humans trying to make meaning out of our time on earth. Why do you think people seek advice? How can we most benefit from the advice of others?

It’s paradoxical, but advice seeking trains us to listen to ourselves. When you listen to someone, you feel resonant or dissonant, right? Being open to advice lends training wheels to our intuition. Plus, we evaluate others better than ourselves because we have more perspective. When questioning another, we can take a step back or away from ourselves, and sometimes that distance brings something into focus.

I do not mean to suggest that we need not listen deeply to each other as well. It’s a far more conscious and invested listening that must take place before one can sense an internal response to another’s statements. In that awareness, though, is something far more valuable than advice. Through it, we connect—with each other, yes—but also with our wisest selves.

Before your brother Jeremy died of cancer at age twenty, he promised to interact with you on earth from the afterlife. And on the morning he died, a rainbow filled the sky. In what other ways have you experienced “a line of communication” with him or others who have passed on?

I’ve experienced several such instances, some of which have shown up in my writing. My essay “Specimen” details an encounter I had with Jeremy when I was involved in a near-fatal car accident after he had been dead for nearly two years. Another, titled “Circle of Willis,” finds an unexpected affinity with the fiction writer Katherine Anne Porter, who also nearly died at age 28 in Denver—though not from a car accident but from the 1918 pandemic.

Artist Kell Black told you, “When you start looking closely at something, you see how everything is connected.” What connections leaped out as you crafted this book?

Kell makes brilliant connections between bodies, history, art, and objects. I would argue this idea if only to connect me to minds like his, but under repeated tests it holds up.

My favorite proof in the book comes from Wendy S. Walters, another radiant artistic mind to draw near. In her writings, she scrutinizes and challenges language, including the narratives of slavery. Reading her work, I recalled the language of climate change, which similarly deflects and denies responsibility. As we discussed this commonality, she found other ways language shapes our thinking and the physical spaces we inhabit, including her home in an asthma zone in Harlem. Acknowledging the influences of language led us to recognize the power of our stories and voices to counter myths and reimagine our characters to offer new means and models.

For me, your book served as a meditation, as it gave me the opportunity to pause and reflect on questions that took me away from the daily grind. How do you incorporate meditation into your daily life?

Oh, that is gratifying to hear, thank you. The book had a similar effect on me, since it inspired a daily meditation practice. The introduction mentions my longtime yoga practice, but I find myself sitting more, and confronting more, even while in movement. The process of integrating varying and often contrary viewpoints is akin to meditation in the sense that we will never harmonize all our disparate voices, but that isn’t the point! Dissonance textures the concert, too, and silence gives it depth, by containing the conflict embedded in music and in us.

As a child, you asked yourself What am I? How have you integrated into your identity some of what you learned from the folks who populate Paper Concert? In other words, how has “the light of the unknowable mystery of the self” become less unknowable for you?

What a profound question, give me a minute.

Okay, I’ll say the book made me aware of something I long suspected, which is that the self is not an individual but a collective. It’s not just that “No man is an island entire of itself,” as Donne said in the days before feminism, but that every island is an ecosystem dependent on countless seen and unseen relationships. Even our eyelashes are networks of interdependent connections! My starting quest for self is clearer now that I’ve gotten to interact directly with some of the voices that shaped me and go on shaping me. What remains engaging about its unknowable mystery is the clearer it becomes, the more you find remains to be explored.

*

Amy Wright is the author of Paper Concert: A Conversation in the Round (Sarabande Books 2021) as well as three poetry books and six chapbooks. She has received two Peter Taylor Fellowships to the Kenyon Review Writers Workshop, an Individual Artist Fellowship from the Tennessee Arts Commission, and a fellowship to Virginia Center for the Creative Arts. Her essays have appeared in Fourth Genre, Georgia Review, Ninth Letter, and elsewhere.

Jenny Patton has had essays cited as notable in the 2016 and 2021 editions of The Best American Essays. She has received the Ohio Arts Council Individual Excellence Award, a Pushcart Prize nomination, a scholarship to the New York Summer Writers Institute, and a Peter Taylor Fellowship to the Kenyon Review Writers Workshop. Her essays have appeared in Iron Horse Literary Review, Brevity, Kaleidoscope, and elsewhere.

No comments:

Post a Comment